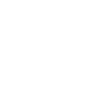

"My Cloak is come home, & here follows the pattern of its' lace. . . . I like it very much," writes Austen to Cassandra while on a six-week visit to the fashionable city of Bath with her parents. This letter is the earliest in the collection to show excisions, presumably by Cassandra after Austen's death, before she bequeathed the letters to their niece Fanny. Biographers suspect that the censored sections of the letters were either overly critical of family members or described indelicate physical ailments too vividly.

Plan your visit. 225 Madison Avenue at 36th Street, New York, NY 10016.

Plan your visit. 225 Madison Avenue at 36th Street, New York, NY 10016.

Search

A Woman's Wit: Jane Austen's Life and Legacy | Selected Images

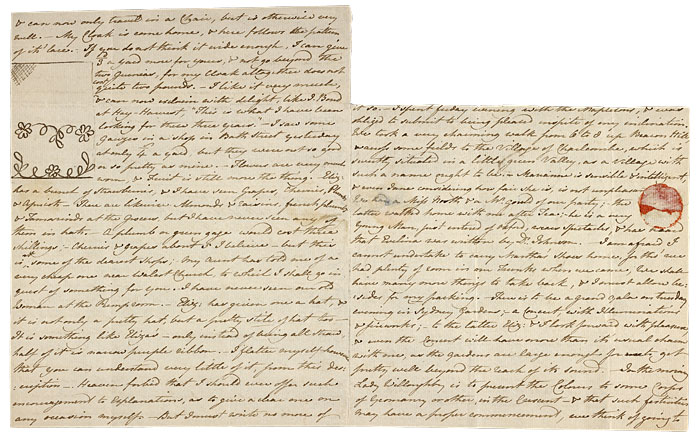

Writing over the course of three days, Austen acknowledges receiving another letter from Cassandra in the meantime: "You are very amiable & very clever to write such long Letters; every page of yours has more lines than this, & every line more words than the average of mine. I am quite ashamed—but you have certainly more little events than we have." The letter is full of little events: "Mr Waller is dead, I see;—I cannot grieve about it, nor perhaps can his Widow very much," and "I want to hear of your gathering Strawberries, we have had them three times here." She reports that she is not enjoying Walter Scott's newest creation Marmion, an epic poem about a sixteenth-century battle between the English and the Scots, although she suspects she should be.

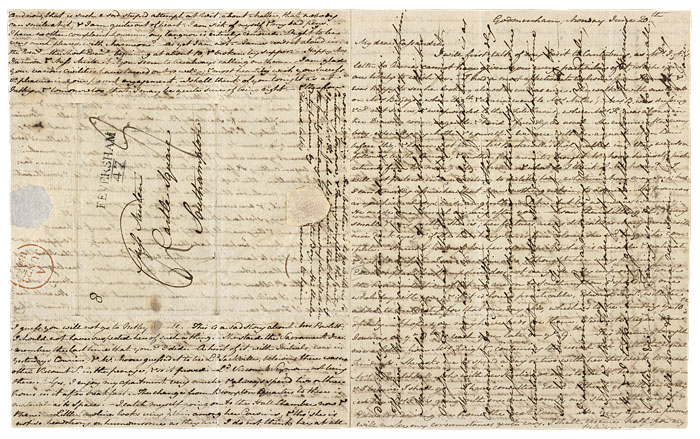

"Plan of a novel" was probably written in 1816 as a comic riposte to Austen's correspondence with James Stanier Clarke, domestic chaplain and librarian to the prince regent. Clarke had self-importantly suggested that Austen write a novel about a clergyman, perhaps modeled on his own career. Austen's "Plan" is an assemblage of cliches and ludicrous plot points—several of which were suggested by the family members, friends, and acquaintances identified in the margins—that exuberantly parodies the implausible, formulaic excesses and artificiality of romantic fiction popular in her time. This pastiche reveals the brilliance of Austen's irony and playful wit.

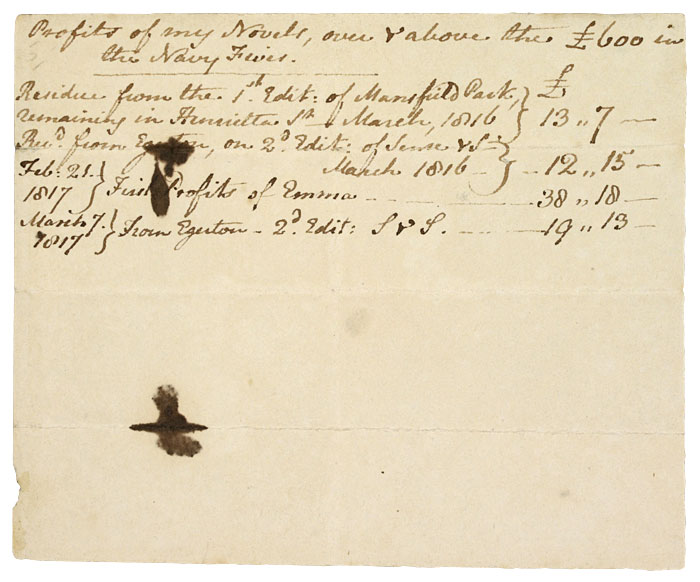

Austen invested the profits of her first three published novels in £600 worth of "Navy Fives," government stock that returned five percent interest annually, bringing her £30 each year. A memorandum of her personal expenditure in 1807 (MA 2911.2), in which she spent over £42, demonstrates that the profits from her novels were not sufficient to support her independently. This note records profits from the sale of Mansfield Park, Sense and Sensibility, and Emma between March 1816 and March 1817. The final entry (7 March 1817) was written only four months before her death, leading the biographer Claire Tomalin to suggest that Austen prepared these accounts when she became ill and began to draft her will.

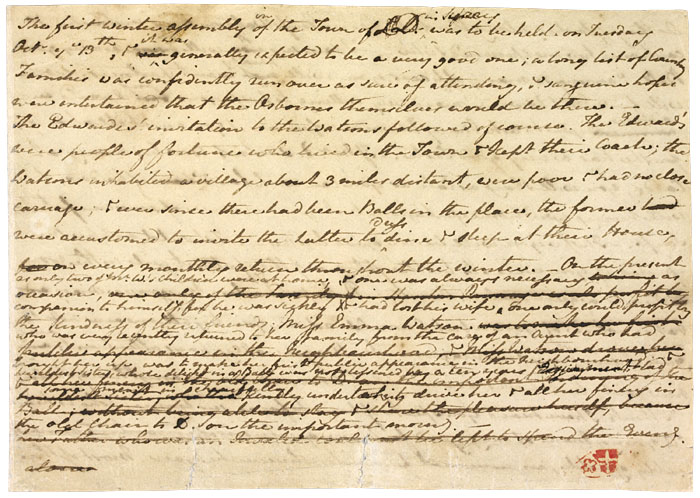

This twelve-page fragment is of enormous significance because it is the only manuscript extant from the period between the completion of Northanger Abbey in 1799 and the beginning of Mansfield Park in 1811 and, unlike the manuscript of Lady Susan, it is a rough draft rather than a fair copy, bearing numerous revisions and cancellations. It was probably begun in 1804 (the paper is watermarked 1803), when Austen was living in Bath. This is a portion of the unfinished novel (the larger portion of the manuscript is held by the University of London). It was given the title "The Watsons" when it was first published by James Edward Austen-Leigh in the 1871 edition of his Memoir. Austen's reasons for abandoning this novel remain conjectural.

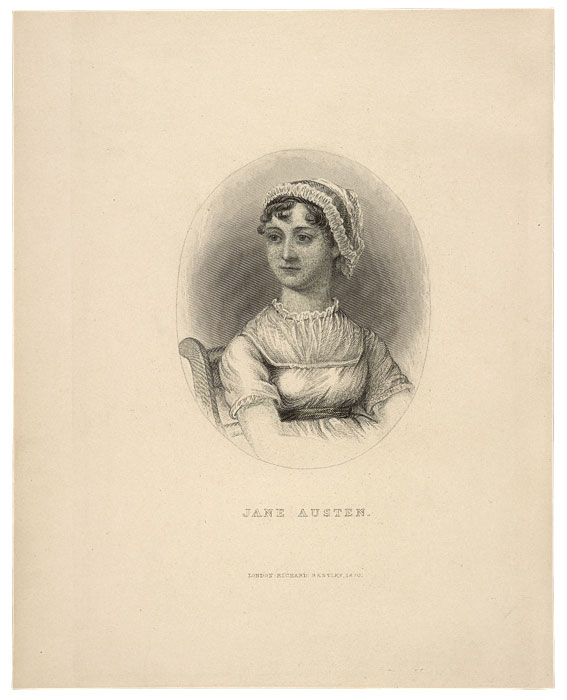

The only life portraits of Jane Austen are two sketches by her sister Cassandra from ca. 1804 and ca. 1810. The later and more famous portrait, an unsigned pencil and watercolor sketch of a hard-set and severe-looking Jane Austen, is now in the National Portrait Gallery, London. J. E. Austen-Leigh commissioned James Andrews to adapt Cassandra's sketch for his Memoir. Andrews's anachronistic watercolor drawing changed Austen's attitude and features, essentially making a more presentable image of the writer for the Victorian reading public. This steel engraving of Andrews's watercolor made Austen's eyes look even larger and milder and her expression more gentle. Austen's niece Cassy Esten Austen commented that this engraving shows "a very pleasing, sweet face, — tho', I confess, to not thinking it much like the original."

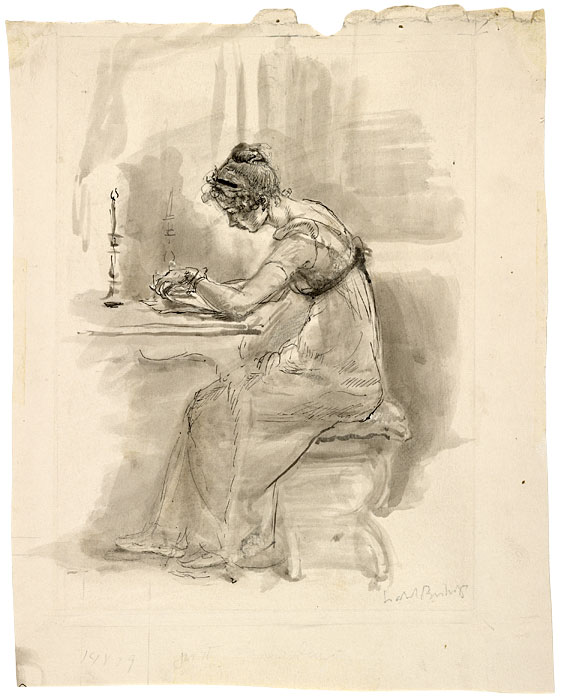

In this scene from Jane Austen's Pride and Prejudice, Elizabeth Bennet is visiting her newlywed friend Charlotte and distant cousin Mr. Collins, and can only communicate with her sister Jane by letter. In reading Jane's letters, Elizabeth realizes Jane is gloomy about Bingley's absence, a situation for which she blames Mr. Darcy. The letters "contained no actual complaint, nor was there any revival of past occurrences, or any communication of present suffering. But in all, and in almost every line of each, there was a want of that cheerfulness which had been used to characterize her style." In a stroke of bad timing, it is just at this moment that Mr. Darcy expresses his love and proposes. Elizabeth cannot hold her tongue: "I had not known you a month before I felt that you were the last man in the world whom I could ever be prevailed upon to marry."

In her letter dated 24 May, 1813 (MA 977.31), Austen reports seeing a painting of how she imagines Jane Bennet, who marries Mr. Bingley at the conclusion of Pride and Prejudice. "Mrs Bingley is exactly herself, size, shaped face, features & sweetness; there never was a greater likeness. She is dressed in a white gown, with green ornaments, which convinces me of what I had always supposed, that green was a favourite colour with her." Scholars suspect that the painting she refers to is the Portrait of Mrs Q by the French portrait painter François Huet-Villiers. Harriet Quentin was a mistress to George IV when he was prince regent. William Blake's 1820 engraving reproduces the portrait.

An unhappily married couple torment each other in the breakfast-room. The lady has left her seat to thump on the piano and sing loudly while her husband sits on the sofa with his hand over his ear, food stuffed into his mouth, reading the 'Sporting Calendar'. The pages of her open music-book are headed 'Forte'. Her song is: 'Torture Fiery Rage / Despair I cannot can not bear'. On the piano lies music: 'Separation a Finale for Two Voices with Accompaniment'; on the floor is ’The Wedding Ring - a Dirge’. A nurse hastens into the room holding a squalling infant, and flourishing a rattle. On the lady’s chair is an open book, ’The Art of Tormenting’, illustrated by a cat playing with a mouse. Under the man’s feet lies a dog barking fiercely at an angry cat, poised on the back of the sofa, and within a hanging birdcage two cockatoos screech angrily at each other, neglecting a nest of three young ones. Beside them on the wall is a bust of ’Hymen’ with a broken nose, and a thermometer that has sunk almost to ’Freezing’. On the chimney-piece is a carved ornament: Cupid asleep under a weeping willow, his torch reversed, the arrows falling from his quiver.

In Austen's letter to Cassandra, written from Bath on 2 June 1799 (MA 977.4), she commented on the style of contemporary hat decorations with evident amusement: "Flowers are very much worn, & Fruit is still more the thing.—Eliz: has a bunch of Strawberries, & I have seen Grapes, Cherries, Plumbs & Apricots—There are likewise Almonds & raisins, french plums & Tamarinds at the Grocers, but I have never seen any of them in hats." Gillray's caricatures satirized ladies who wore enormous ostrich feathers that needed to be glued in place with large quantities of goose grease and hair powder.

In the eighteenth century, wealthy landowners commissioned artists to record the appearance of their estates, which were often a tribute to their personal taste. The exact location of Sandby's watercolor view is unidentified, but it is representative of the topography of the parks in which Austen's novels take place, such as Donwell Abbey in Emma, with its "abundance of timber in rows and avenues, which neither fashion nor extravagance had rooted up." Austen's brother Henry remembered, in his "Biographical Notice" (1818), published with the first editions of Persuasion and Northanger Abbey, that his sister was "a warm and judicious admirer of landscape, both in nature and on canvas."

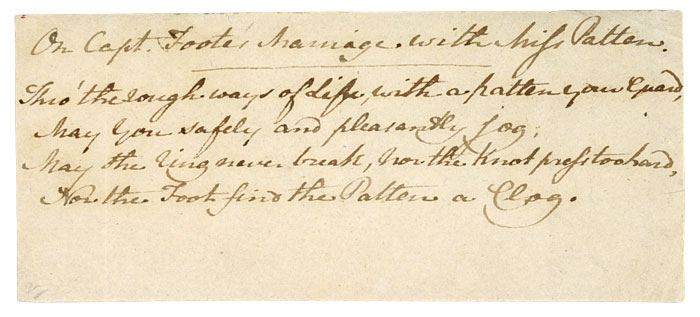

In Austen's time poetry was regarded as a more serious genre than prose fiction. Austen seems to have inherited her poetic talent from her mother, but she did not consider herself to be a serious poet and generally wrote occasional poems for events, such as marriages and births, that were playful, comic, or celebratory. For Austen, reading poetry was a serious pursuit, but her own compositions were a lighthearted pastime for personal and family amusement rather than publication. Eighteen poems by Austen—not all in her hand—survive. It is likely that she wrote many others that were subsequently lost or remain untraced. Although this poem is in Austen's handwriting, it was composed by her uncle James Leigh Perrot. Her final poem was written three days before her death.